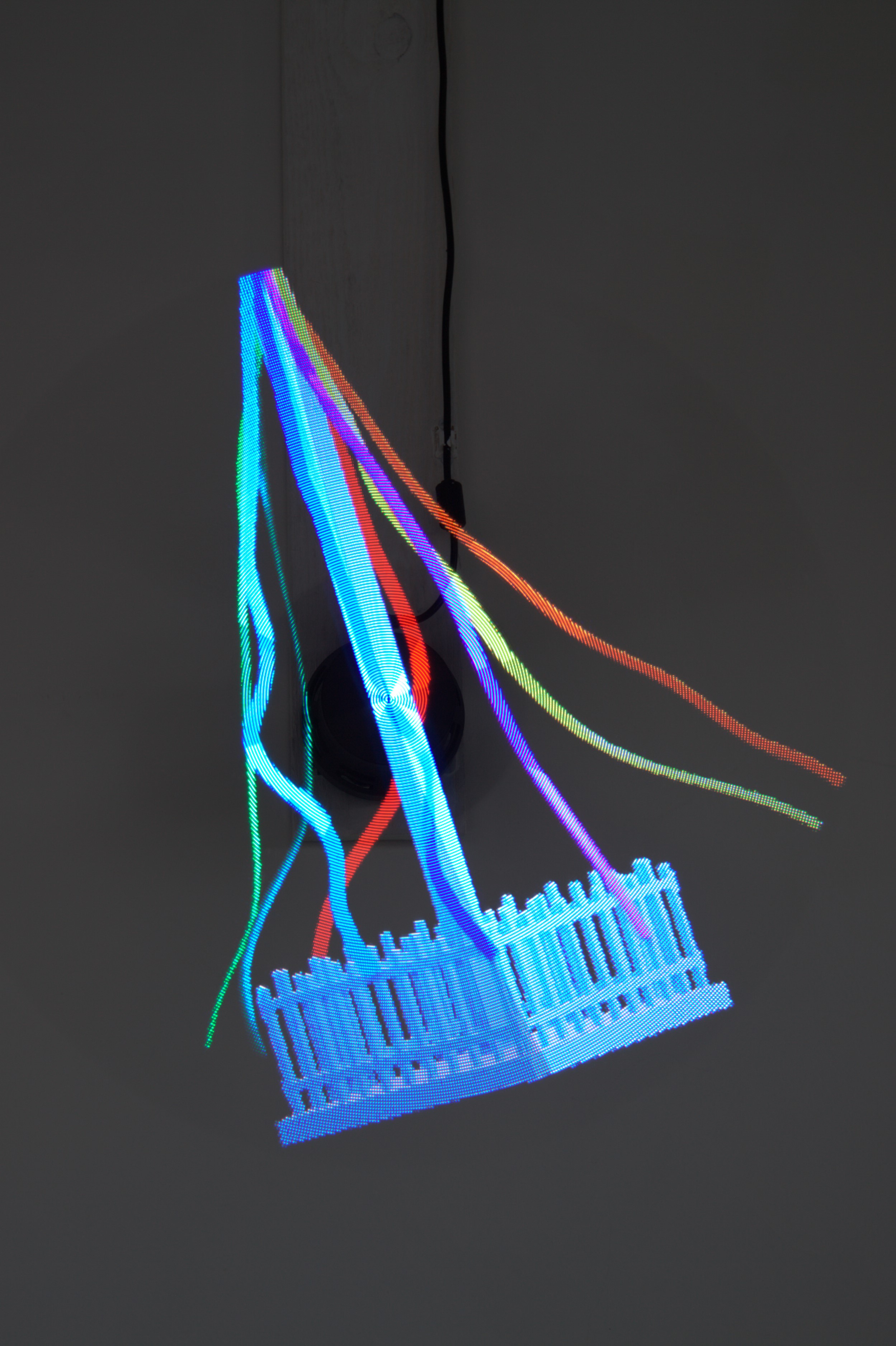

ROADSIDE OBJECTS

photographic series : plexiglas printing, 3D projector

Copenhagen Photo Festival

/ 2024. Copenhagen. DK

Festival Circulation(s). CENTQUATRE-PARIS / 2025. Paris, FR

Working with archival photography and the history of everyday life, Lesia Pcholka turned to the well-known works of Belarusian ethnographers. Pcholka's series of photographs ‘Roadside objects’ is inspired by Mikhail Romanyuk's monograph ‘Belarusian Folk Crosses’ (2000), which is the culmination of 30-plus years of meticulous research and documentation of Belarusian funerary and roadside crosses. The crosses, which were usually placed on roadsides in villages or at crossroads, were intended to protect people from epidemics, wars and natural disasters. These objects organically combine elements of both Christian and pagan beliefs, which is a characteristic feature of Belarusian spirituality.

In today’s fraught political climate, studying Belarusian ethnography and culture has become increasingly complex. Contemporary researchers are forced to rely on the knowledge of 40-50 years ago, without understanding whether and how the rituals have been preserved and transformed. They are forced to rely on the subjective narratives of ethnographers (more often men) as well as black and white photographs. That is why, for her research, Pcholka created three maps, marking all the points (villages) where the photos were taken for Romaniuk's book. And she conducted three expeditions in search of the wooden crosses documented in the book. Ultimately, she could not find any crosses depicted in the book. The crosses most likely disappeared through natural means, or to make way for updated versions. Indeed, many were replaced by new ones, most often metal, decorated by local people, reflecting their individual knowledge and aesthetic preferences. The eclectic appearance, with its use of contemporary detail, influenced Pcholka’s choice of a contemporary photographic language to document these objects.

Everyday rituals tend to be overshadowed by political conflicts. Further, these rituals are inscribed in a sphere of community life that is reproduced with a social rather than a religious connotation. Today, in Belarus, the space of everyday life is the space that remains for the people to express themselves in. Pcholka believes that heritage is a dynamic and discursive construct. References to monographs created half a century ago create more distance between researchers’ understanding of the community. To this end, in Pcholka's photographs, the crosses become removed from the landscape and seem to hang in the air, emphasizing their alienation and timelessness. Emerging like flashes on the roadside, their brightly colored ribbons and flowers are more likely to be associated with queer pride than with the patriarchal past. While they may have lost their original meaning long ago, the crosses are not only sustained, but also replicated through an uncoordinated, iterative, and vibrant social practice.